Christine Pearson

A single incident of incivility in the workplace can result in significant operational costs, reported Christine Pearson of Thunderbird School of Global Management and Christine Porath of Georgetown University.

Additional consequences of workplace incivility include:

- Decreased work effort due to disengagement,

Christine Porath

- Less time at work to reduce contact with offensive co-workers or managers,

- Decreased work productivity due to ruminating about incivility incidents,

- Less commitment to the organization,

- Attrition.

P.M. Forni

Other organizational symptoms include:

- Increased customer complaints,

- Accentuated cultural and communications barriers,

- Reduced confidence in leadership,

- Less adoption of changed organizational processes,

- Reduced willingness to accept additional responsibility and make discretionary work efforts.

Workplace incivility behaviours were described as “rude and discourteous, displaying a lack of regard for others,” noted Pearson and Lynne Andersson, then of St. Joseph’s University.

“Uncivil” behaviors were enumerated in The Baltimore Workplace Civility Study by Johns Hopkins’ P.M. Forni and Daniel L. Buccino with David Stevens and Treva Stack of University of Baltimore:

- Refusing to collaborate on a team project,

- Shifting blame for an error to a co-worker,

- Reading another’s mail,

- Neglecting to say “please,” “thank you”,

- Taking a co-worker’s food from the office refrigerator without asking.

Respondents classified more extreme unacceptable behaviors:

- Pushing a co-worker during an argument,

- Yelling at a co-worker,

- Firing a subordinate during a disagreement,

- Criticising a subordinate in public,

- Using foul language in the workplace.

Gary Namie

Workplace bullying was included in Gary Namie’s Campaign Against Workplace Bullying.

He defined bullying as “the deliberate repeated, hurtful verbal mistreatment of a person (target) by a cruel perpetrator (bully).

His survey of more than 1300 respondents found that:

- More than one-third of respondents observed bullying in the previous two years,

- More than 80% of perpetrators were workplace supervisors,

- Women bullied as frequently as men,

- Women were targets of bullying 75% of the time,

- Few bullies were punished, transferred, or terminated from jobs.

Costs of health-related symptoms experienced by bullying targets included:

- Depression,

- Sleep loss, anxiety, inability to concentrate, which reduced work productivity,

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among 31% of women and 21% of men,

- Frequent rumination about past bullying, leading to inattention, poor concentration, and reduced productivity.

Widespread prevalence of workplace incivility was also reported by Forni, who suggested ways to improve workplace interactions and inclusion:

Widespread prevalence of workplace incivility was also reported by Forni, who suggested ways to improve workplace interactions and inclusion:

- Assume that others have positive intentions,

- Pay attention, listen,

- Include all co-workers in workplace activities,

- Acknowledge others,

- Give praise when warranted,

- Respect others’ opinions, time, space, indirect refusals,

- Avoid asking personal questions,

- Be selective in asking for favors,

- Apologize when warranted,

- Provide constructive suggestions for improvement instead of complaints,

- Maintain personal grooming, health, and work environment,

- Accept responsibility for undesired outcomes, if deserved.

More than 95% of respondents in The Baltimore Workplace Civility Study suggested, “Keep stress and fatigue at manageable levels,” a challenging goal for leaders who shape workplace cultures.

Organizational change recommendations include:

- Institute a grievance process to investigate and address complaints of incivility,

- Select prospective employees with effective interpersonal skills,

- Provide a clearly-written policy on interpersonal conduct,

- Adopt flexibility in scheduling, assignments, and work-life issues.

-*How do you handle workplace incivility when you observe or experience it?

©Kathryn Welds

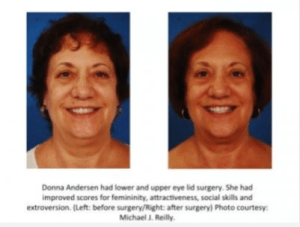

Raters assigned higher scores for likeability, social skills, and attractiveness to the images following plastic surgery compared with pre-surgery image ratings.

Raters assigned higher scores for likeability, social skills, and attractiveness to the images following plastic surgery compared with pre-surgery image ratings.