-*Do you re-enact scenarios from your past, but with different people?

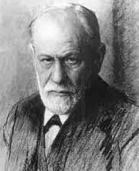

Sigmund Freud described this experience as “transference,” redirecting feelings toward one person in the past onto a different individual in the present.

The current recipient of feelings may have different characteristics, motivations, and behaviours than the original person, but something about the present individual triggers earlier feelings and actions.

NYU’s Susan Andersen and Alana Baum demonstrated transference in lab studies when they asked volunteers to describe important people in their lives for whom they had positive feelings or negative feelings.

They also described other people’s significant others.

Later, Anderson and Baum described a person seated in the next room, using either emotionally-positive or emotionally-negative descriptions of someone from the volunteer’s life or someone else’s life.

Participants more accurately recalled the stranger’s description when it resembled their own significant other.

Recall was enhanced because the significant other’s description was memorable, suggesting transference.

Biased inference can result from a memory’s “accessibility” and distinctiveness, according to Anderson’s collaborators Steve W. Cole and Noah Glassman.

Transference is an outgrowth of attachment to others in the past, according to Queens College’s Claudia Chloe Brumbaugh and R. Chris Fraley University of Illinois.

In their study, participants read profiles of two potential dating partners: One description resembled a romantic partner from the person’s past, and another description matched a different participant’s former partner.

Volunteers reported feeling more comfortable and more anxious toward potential dating partners described as similar to previous significant others.

Brumbaugh and Fraley noted that participants “applied attachment representations of past partners” to any potential future partner, and when the new partner’s description resembled an important past partner.

Susan Fiske

Princeton’s Susan Fiske described this transfer of affective responses to a new individual as schema-triggered affect.

Andersen used this framework and a socio-cognitive explanation in a paper with Berkeley’s Serena Chen.

People modify views of themselves and others in transference situations, reported Katrina Hinkley and Andersen.

In their research, volunteers demonstrated biased recall about a new person when they were reminded of an earlier significant other.

When participants were re-tested, their lists of the new person’s attributes included elements of themselves when they had been with the former significant person.

Transference occurs even when a target person possesses an attribute incompatible with the significant other’s characteristics, found University of Illinois’s Michael W. Kraus with Berkeley’s Chen, Victoria A. Lee, and Laura D. Straus.

Participants demonstrated transference in biased memories and judgments about a person they perceived as similar to a former significant other.

The research team elicited positive impressions even when the target was from a different ethnic group.

This suggests that stigma and discrimination may be reduced by evoking positive transference from past experiences to present actors.

Baum and Anderson observed that participants’ current mood was more positive when the target of their transference resembled their significant other and occupied a similar role to the original person.

Transference in the workplace can be problematic when employees react to one another as they responded to others from the past, introducing unconscious emotional elements to work situations.

-*How do you manage transference reactions in work and social situations?

RELATED POSTS:

- Biases in Unconscious Automatic Mental Processing, and “Work-Arounds”

- How Sure are You of Your “Memories”? Suggestibility, Insertion, and Construction of Recall

- Knowing without Knowing – Implicit Learning in Action

©Kathryn Welds