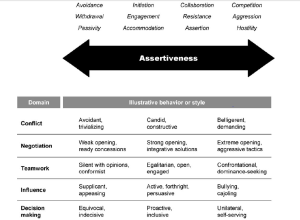

Negotiation assertiveness style can determine success in bargaining, according to Columbia University’s Daniel Ames and Abbie Wazlawek.

They found that most people do not accurately assess others’ view of their assertiveness in specific situations.

Over-assertive individuals tend to have less-accurate self-perception than less assertive people, and both groups experience “self-awareness blindness.”

These inaccurate self-perceptions may develop from polite yet inaccurate feedback from other people.

Self-awareness resulted in most favorable negotiation outcomes.

More than 80% of negotiators rated by others and by themselves as “appropriately assertive in the situation” negotiated greatest value to both parties.

When negotiation partners misperceived others’ view of their exaggerated objections (strategic umbrage), Ames and Wazlawek called this experience the line-crossing illusion.

This mismatch between negotiation partners’ ratings of appropriate assertiveness was linked to poorer negotiation outcomes.

Nearly 60% of negotiators who were rated as appropriately assertive but felt over-assertive (line-crossing illusion) negotiated the inferior deals for themselves and their counterparts.

This finding suggests that disingenuous emotional displays of strategic umbrage lead negotiation partners to seek the first acceptable deal, rather than pushing for an optimal deal.

To improve accuracy of perception of other people’s impression of one’s own assertiveness style (“meta-perception“), Ames and Wazlawek suggested:

-Participate in 360 degree feedback,

-Increase skill in listening for content and meaning,

–Consider whether negotiation proposals are “reasonable” in light of alternatives,

-Request feedback on reactions to “strategic umbrage” displays to better understand perceptions of “offer reasonableness,”

-Evaluate costs and benefits of specific assertiveness styles.

Gary Yukl

Over-assertiveness may provide the benefit of “claiming value” in a negotiation but may lead to ruptured interpersonal relationships, according to Jeffrey M. Kern of Texas A&M, SUNY’s Cecilia Falbe and Gary Yukl.

Cultural norms for assertiveness regulation in “low context” cultures like Israel, where dramatic displays are frequent and expected in negotiations.

In contrast, “high context” cultures like Japan, require more nuanced assertiveness, with fewer direct disagreements and “strategic umbrage” displays, according to Edward T. Hall, then of the U.S. Department of State.

Under-assertiveness may minimize interpersonal conflict, but may lead to poorer negotiation outcomes and undermined credibility in future interactions, according to Ames’ related research.

To augment a less assertiveness style, he suggested:

- Set slightly higher goals,

- Reconsider assumptions that greater assertion leads to conflict,

- Increase proactivity to show respect and improve outcomes,

- Observe outcomes when collaborating with more assertive other people.

To modulate a more assertiveness style:

- Make slight concessions to increase trust with others,

- Evaluate the outcomes when collaborating with less assertive other people.

The line-crossing illusion is an example of a self-perception bias in which personal ratings of behavior may not match other people’s perceptions, and others’ behaviors can reduce one’s own confidence and assertiveness.

*How do you reduce the risk of developing the line-crossing illusion in response to other people’s displays of “strategic umbrage”?

*How do you match your degree of assertiveness to negotiation situations?

RELATED POSTS:

- How Effective are Strategic Threats, Anger, and Unpredictability in Negotiations?

- Expressing Anger at Work: Power Tactic or Career-Limiting Strategy?

- Anxiety Undermines Negotiation Performance

- Power Tactics for Better Negotiation

- Do You Accept Bad Deals?

- Decision Maximizers, Satisficers and Potential Bias

- “Honest Confidence” Enables Performance, Perceived Power

©Kathryn Welds