Communication, “Gravitas”, and Appearance were frequently-cited attributes of Executive Presence in a study by Sylvia Ann Hewlett of the Center for Talent Innovation.

Gavin Dagley

More characteristics of executive presence were identified in interviews with 34 professionals, conducted by Perspex Consulting’s Gavin Dagley and Cadeyrn J. Gaskin, formerly of Deakin University.

Caderyn Gaskin

Five “executive presence” qualities were observable during initial contact:

- Status and reputation, similar to “gravitas” discussed by Hewitt,

- Physical appearance, mentioned by Hewitt,

- Confidence,

- Communication ability, included in Hewitt’s “executive presence” triad,

- Interpersonal engagement skills.

Five additional presence features emerged during repeated contacts:

- Interpersonal integrity,

- Values-in-action,

- Intellect and expertise,

- Outcome delivery,

- Use of coercive power.

These qualities combine in different ways to form four presence “archetypes”:

- Positive presence, based on favorable impressions of confidence, communication, appearance, and engagement skills plus favorable evaluations of values, intellect, and expertise,

- Unexpected presence, linked to unfavorable impressions of confidence plus favorable evaluations of intellect, expertise, and values,

- Unsustainable presence combines favorable impressions of confidence, status, reputation, communication, and engagement skills plus unfavorable evaluations of values and integrity,

- “Dark presence” is associated with unfavorable perceptions of engagement skills plus unfavorable evaluations of values, integrity, and coercive use of power.

Another typology of executive presence characteristics was identified by Sharon V. Voros and Bain’s Philippe de Backer.

They prioritized elements in order of importance for life outcomes:

- Focus on long term strategic drivers,

- Intellect,

- Charisma, comprised of confidence, intensity, commitment, care, concern and interest in others,

- Communication skills,

- Enthusiasm for work,

- Cultural fit with organisation and team,

- Poise,

- Appearance.

University of Nebraska’s Fred Luthans and Stuart Rosenkrantz with Richard M. Hodgetts of Florida International University investigated the relationship between “executive presence” and career “success.”

These researchers observed nearly 300 managers across levels at large and small mainstream organizations when leaders:

- Communicated,

- Engaged in “traditional management” activities, including planning, decision making, controlling,

- Managed human resource issues.

Communication and interpersonal skills, coupled with intentional networking and political acumen enabled some managers to rapidly advance in their organizations.

These rapidly-advancing managers were identified as “successful” leaders because they achieved a higher organizational level compared with their organizational tenure.

In contrast, “effective” managers demonstrated greater managerial skill than “successful” managers, but were not promoted as quickly.

“Effective” managers spent most time managing employees’ activities including:

- Motivating and reinforcing desired behaviours,

- Managing conflict,

- Hiring,

- Training and developing team members,

- Communicating by exchanging information,

- Processing paperwork.

Subordinates of “effective” managers reported more:

- Job satisfaction,

- Organizational commitment,

- Performance quality,

- Performance quantity.

Differences in advancement and subordinate reactions to “successful” and “effective” managers were related to differing managerial behaviors.

“Successful” managers spent little time in managerial activities, but invested more effort in networking, socializing, politicking, and interacting with outsiders.

“Successful” managers spent little time in managerial activities, but invested more effort in networking, socializing, politicking, and interacting with outsiders.

Their networking activities were most strongly related to career advancement but weakly associated with “effectiveness.”

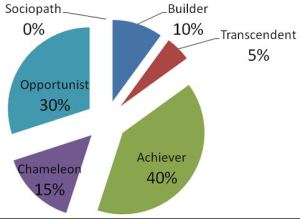

Few managers were both “successful” and “effective”:

Only about 10% leaders were among the top third of successful managers and effective managers.

This suggests that effective managers who support employee performance may not be advance as rapidly as managers who prioritize their own career over their employees’ careers.

Gender differences in gravitas, communication, and political acumen may explain why men more often are seen as possessing “executive presence.”

Women who aspire to organizational advancement benefit from cultivating both gravitas and proactive networking to complement communication and interpersonal skills.

-*Which behaviors and characteristics are essential to “Executive Presence?”

Related Posts

- Executive Presence: “Gravitas”, Communication…and Appearance?

- Leadership Qualities that Lead to the Corner Office

- Powerful Non-Verbal Behavior May Have More Impact Than a Good Argument

- Authoritative Non-Verbal Communication for Women in the Workplace

- How Much Does Appearance Matter?

- Developing “Charisma” and “Presence”

- Attractiveness Bias in Groups

- How Accurate are Personality Judgments Based on Physical Appearance?

- “Self-Packaging” as Personal Brand: Implicit Requirements for Personal Appearance?

- Non-Verbal Behaviors that Signal “Charisma”

©Kathryn Welds