Ethan Kross

Despite years of popular guidance to use self-statements for difficult conversations with partners, spouses, and bosses, research argues for using self-distancing alternatives to manage stress and increase self-control.

Emma Bruehlman-Senecal

University of Michigan’s Ethan Kross, Jiyoung Park, Aleah Burson, Adrienne Dougherty, Holly Shablack, and Ryan Bremner with Emma Bruehlman-Senecal and Ozlem Ayduk of University of California, Berkeley, plus Michigan State’s Jason Moser studied more than 580 people’s ability to self-regulate reactions to social stress by using different ways of referring to the self during introspection.

LeBron James

One example of variations in self-reference is LeBron James’ statement, “One thing I didn’t want to do was make an emotional decision. I wanted to do what’s best for LeBron James and to do what makes LeBron James happy.”

The team demonstrated that using non-first-person pronouns (such as “he” or “she”) and one’s own name (rather than “I”) during introspection enhanced self-distancing, or focusing on the self from a distant perspective.

Stephen Hayes

Distancing, also called “decentering” or “self as context,” allows people to observe and accept their feelings, according to University of Nevada’s Steven Hayes, Jason Luoma, Akihiko Masuda and Jason Lillis collaborating with Frank Bond of University of London.

Ozlem Ayduk

Self-distancing verbalizations were associated with less distress and less maladaptive “post-event processing” (reviewing performance) when delivering a speech without sufficient time to prepare, and when seeking to make a good first impression on others.

Post-event processing can lead to increased social anxiety, noted Temple University’s Faith Brozovich and Richard Heimberg.

Faith Brozovich

They found that participantsexperienced less global negative affect and shame after delivering a speech without sufficient preparation time, and engaged in less post-event processing.

Adrienne Dougherty

People who talked about themselves with non-first person pronouns also performed better in speaking and impression-formation social tasks, according to ratings by observers.

Participants who used self-distancing language appraised future stressors as less threatening, and they more effectively reconstrued experiences for greater coping, insight, and closure, in another study by Kross and Ayduk.

Ryan Bremner

People with elevated scores on measures of depression or bipolar disorder experienced less distress when applying a self-distanced visual perspective as they contemplated emotional experiences, noted Kross and Ayduk, collaborating with San Francisco State University’s David Gard, Patricia Deldin of University of Michigan, and Jessica Clifton of University of Vermont.

David Gard

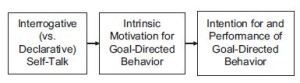

Using second-person pronouns (“you”) seems to be a self-distancing strategy when people reflect on situations that involve self-control, noted University of North Carolina’s Ethan Zell, Amy Beth Warriner of McMaster University and University of Illinois’s Dolores Albarracín.

Ethan Zell

These findings demonstrate that small changes in self-referencing words during introspection significantly increase self-regulation of thoughts, feelings, and behavior during social stress experiences.

Self-distancing references may help people manage depression and anger about past and anticipated social anxiety.

Dolores Albarracín

-*What impact do you experience when you use “self-distancing language”?

-*How do you react when you hear others using “self-distancing language,” like referring to “you” when speaking about their own experience?

Related Posts:

- Most Effective “Calls to Action” Are Aligned to Audience “Construal Level”, Psychological Distance”

- Power of “Powerless” Speech, but not Powerless Posture

- Thinking in a Second Languages Reduces Decision Bias

- Gender-Neutral Language Associated with Greater Gender Wage Parity

- Change Future Time Perspective to Reduce Procrastination

- Creating Productive Thought Patterns through “Thought Self-Leadership”

- Reduce Rumination, Stress by Taking a Walk in Nature, Viewing Animals