People can improve task performance in public speaking, mathematical problem solving, and karaoke singing, by reappraising anxiety as “excitement,” according to Harvard’s Alison Wood Brooks.

Using silent self-talk messages (“I am excited”) or reading self-direction messages (“Get excited!”) fosters an “opportunity mind-set” by increasing alignment between physical arousal and situational appraisal.

Jeremy Jamieson

“Excitement” is typically viewed as a positive, pleasant emotion that can improve performance, according to Harvard’s Jeremy Jamieson and colleagues.

In contrast, anxiety drains working memory capacity, and decreases self-confidence, self-efficacy, and performance before or during a task, according to Michael W. Eysenck of University of London.

Despite these differences, anxiety and excitement have similar physiological arousal profiles, but different effects on performance.

Michael Eysenck

Efforts to transform anxiety into calmness can be ineffective due to the large shift from negative emotion to neutral or positive emotion and from physiological activation to lower arousal levels, noted Brooks.

Such efforts to calm physiological arousal during anxiety can result in a paradoxical increase in the suppressed emotion, reported Stefan Hofmann and colleagues of Boston University.

However, most people in Woods’ studies said they believed that this is the best way to handle anxiety.

Physiological similarities can confuse experiences of anxiety and excitement, demonstrated in studies by Columbia’s Stanley Schacter and Jerome Singer of SUNY.

Anxiety’s similarity to excitement can be used to relabel high “anxiety” as “excitement.”

This shift can mitigate anxiety’s negative impact on performance.

Brooks elicited anxiety among volunteers by telling them that they their task was to present an impromptu, videotaped speech.

For some participants, she explained that it is “normal” to feel discomfort and asked them to “take a realistic perspective on this task by recognising that there is no reason to feel anxious” and “the situation does not present a threat to you…there are no negative consequences...”

She also instructed volunteers to say aloud randomly-assigned self-statements like “I am excited.”

People who stated “I am excited” before their speech were rated as more persuasive, more competent, more confident, and more persistent (spoke longer), than participants who said “I am calm.”

Brooks evaluated peoples’ reactions to another anxiety-provoking task, performing a karaoke song for an audience, and rated by voice recognition software for “singing accuracy” based on:

- Volume (quiet-loud),

- Pitch (distance from true pitch),

- Note duration (accuracy of breaks between notes).

This score determined participants’ payment for participating in the study.

Before performing, she asked participants to make a randomly-assigned self-statement:

- “I am anxious,”

- “I am excited,”

- “I am calm,”

- “I am angry.”

- “I am sad.”

- No statement.

Following their performance, volunteers rated their anxiety, excitement, and confidence in their singing ability.

People who said that they were “excited” had higher pulse rates than other groups, confirming that self-statements can affect physical experiences of emotion.

Volunteers who said “I am excited” had the highest scores for singing accuracy and also for confidence in singing ability.

In contrast, those who said, “I am anxious” had the lowest scores for singing accuracy, suggesting that anxiety is associated with lower performance.

Brooks elicited anxiety on “a very difficult IQ test…under time pressure” that would determine their payment for participation.

To evoke further anxiety, she concluded, “Good luck minimising your loss.”

Before the test, participants read a statement:

- “Try to remain calm” or

- “Try to get excited.”

Those instructed to “get excited” produced more correct answers than those who tried to “remain calm.”

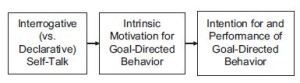

Reappraising anxiety as “excitement” increased the subjective experience of “excitement” instead of anxiety, and improved subsequent performance in each of these tasks.

These reappraisals of physical experiences evoked an “opportunity mind-set” and a “stress-is-enhancing” mind-set, found University of Toronto’s Stéphane Côté and Christopher Miners.

These appraisals enabled superior performance across different anxiety-arousing situations.

In contrast, inauthentic emotional displays can be physically and psychologically demanding, and often reduce performance.

People have “profound control and influence…over…emotions,” according to Woods.

She noted that “Saying ‘I am excited’ represents a simple, minimal intervention…to prime an opportunity mind-set and improve performance…

Advising employees to say ‘I am excited’ before important performance tasks or simply encouraging them to ‘get excited’ may increase their confidence, improve performance, and boost beliefs in their ability to perform well in the future.”

-*How effective have you found focusing on “excitement” instead of “calm” in managing anxiety?

RELATED POSTS:

- Beware of Seeking, Acting on Advice When Anxious, Sad

- Asking Yourself Questions Enhances Performance

- Creating Productive Thought Patterns

- Self Compassion, not Self-Esteem, Enhances Performance

©Kathryn Welds