People who change gender continue to draw upon their education and experience to perform at work. However, many of these people report that their compensation, degree of respect, and recognition at work changed following gender change. This suggests that gender can directly affect compensation and workplace interactions.

Two Stanford professors’ experience in gender transition were highlighted by University of Chicago’s Kristen Schilt.

Stanford’s Joan Roughgarden, was an evolutionary biologist for more than 25 years as Jonathan Roughgarden before she made her male-to-female (MTF) transition.

Known for her work integrating evolutionary theory with Christian beliefs (“theistic evolutionism”), she reported feeling less able to make bold hypotheses and no longer had “the right to be wrong.”

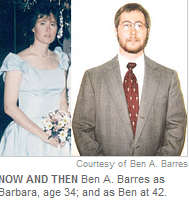

Her experience contrasts with Stanford colleague, neurobiologist Ben Barres, who made scientific contributions as Barbara Barres until after he was 40.

After his female-to-male (FTM) transition, Ben delivered a lecture at the Whitehead Institute, where an audience member commented, “Ben Barres gave a great seminar today, but, then, his work is much better than his sister’s.”

Schilt surveyed FTM and MTF to compare earnings and employment experiences before and after gender transitions with questions similar to 2002 Current Population Survey (CPS) survey items:

- Last job before gender transition,

- First job after gender transition,

- Most recent job.

Female-to-male transsexuals (FTMs) reported that as men, they had more authority, reward, and respect in the workplace than they received as women, even when they remained in the same jobs.

Height and skin color affected potential advantages enjoyed by FTM.

Tall, white FTMs experienced greater benefits than short FTMs and FTMs of color.

In contrast, MTF reported reduced authority and pay, and often harassment and termination.

University of Illinois’s Donald McCloskey, for example, was told by his department chair “in jest” that he could expect a salary reduction when he became Deirdre McCloskey.

However, salary reduction was no joke for MTFs in Schilt’s survey sample.

Participants reported significant losses of 12% in hourly earnings after becoming female.

Additionally, MTFs transitioned on average 10 years later than FTMs, delaying the loss of labor market advantages attributable to male gender.

FTMs, however, experienced no change in earnings or small positive increases up to 7.5% in earnings after transitioning to becoming men.

Any gender transition was associated with risks of harassment and discrimination, reported more frequently in “blue-collar” jobs, particularly for those with “non-normative” appearance and not consistently “passing” as the other gender.

These “naturalistic experiments” confirm continuing gender-based pay discrepancies.

-*To what extent have you observed these gender-linked differences in compensation and workplace credibility?

RELATED POSTS:

- “Social Accounts” as Pay Substitutes for Women

- How Accurate are Personality Judgments Based on Physical Appearance?

- “Self-Packaging” as Personal Brand: Implicit Requirements for Personal Appearance?

- Role Pioneers May Encounter “The Glass Cliff”

- Women Don’t Ask for Raises or Promotions as Often as Men

- Attractive Appearance Helps Men Gain Business Funding

- Executive Presence: “Gravitas”, Communication…and Appearance?

- How Much Does Appearance Matter?

©Kathryn Welds